Culture and Socially Engaged Practices in Yogja

Freedom came for Indonesia a second time in 1998, with the overthrowing of Suharto’s repressive New Order regime. The Reformasi ignited an explosion of arts and creative expression in the country: a burst led by many artists and intellectuals— a number of whom were involved in the struggle for change. New arts collectives emerged and numerous exciting international events started taking place annually throughout Indonesia. In Yogja, the mixture of history, culture, environment and the presence of important universitie,s including the Indonesian Institute for Arts, helped foster a dense ecosystem of arts spaces and events, and a set of cutting edge practises have emerged in this melange.

In this piece, I will highlight some issues related to freedom and to the role of cultural practitioners in Indonesia. Then I will introduce you to six organisations which are in operation in Yogyakarta and their successful response to some of these issues. The organisational features of these bodies will be highlighted and I'll and conclude by talking about some of the success and challenges of collectives as a response to the Yogja context.

Freedom and the challenge of change

As often happens, freedom comes with unintended consequences. In the case of Indonesia,it enabled conservative Islamic groups to flourish and led to a wave of intolerance, abetted by global fundamentalist influences. It also opened the way for a greater inflow of corporates, an increased degradation of the environment and a resultant large-scale destruction of Indonesian’s bio-diversity. Corruption was made visible, rules were relaxed, opportunities ruthlessly taken. The end result is further limits to personal freedom and growing insecurities amongst many communities. These fears are not unwarranted. Despite a friendly society, violence is something that simmers under the surface as was seen in previous article. The country has yet to discuss productively, let alone come to terms, with the genocide that took place in 65/66 against the left nor the xenophobic attacks against ethnic Chinese in 1998.

Indonesia is a country struggling with intense poverty - although there has been significant improvements since 1999, over 10% of the 252 million Indonesians still live below the poverty line and 40% of the population "remain vulnerable of falling into poverty, as their income hover marginally above the national poverty line". Job creation and economic growth are well below the growth of the population. Indonesia has one of the highest (and growing) levels of inequality in the world. It has a large youth population with 24.42% under 15. 17% of the population is between 15-24, and there are few opportunities as they enter the job market. The legacies of colonisation, dictatorship and ongoing corruption, play a big role in impeding these changes.

The Role of Artists

It’s in this context of extreme economic, environmental and societal challenges that the role of artists becomes even more complex, raising important issues of ethics and responsibilities. One of the places where work can done is working with culture and memory - helping people to come to terms with the past, to feel empowered as individuals and as communities and so to realise new visions for the future. In this context fostering creativity, respect for openness and of human, cultural and environmental rights are vital.

Popular Cultural Expressions. One of a number of pedicabs, modified with neon, sound systems and other accessories which families use when enjoying a public space Alun Alun.

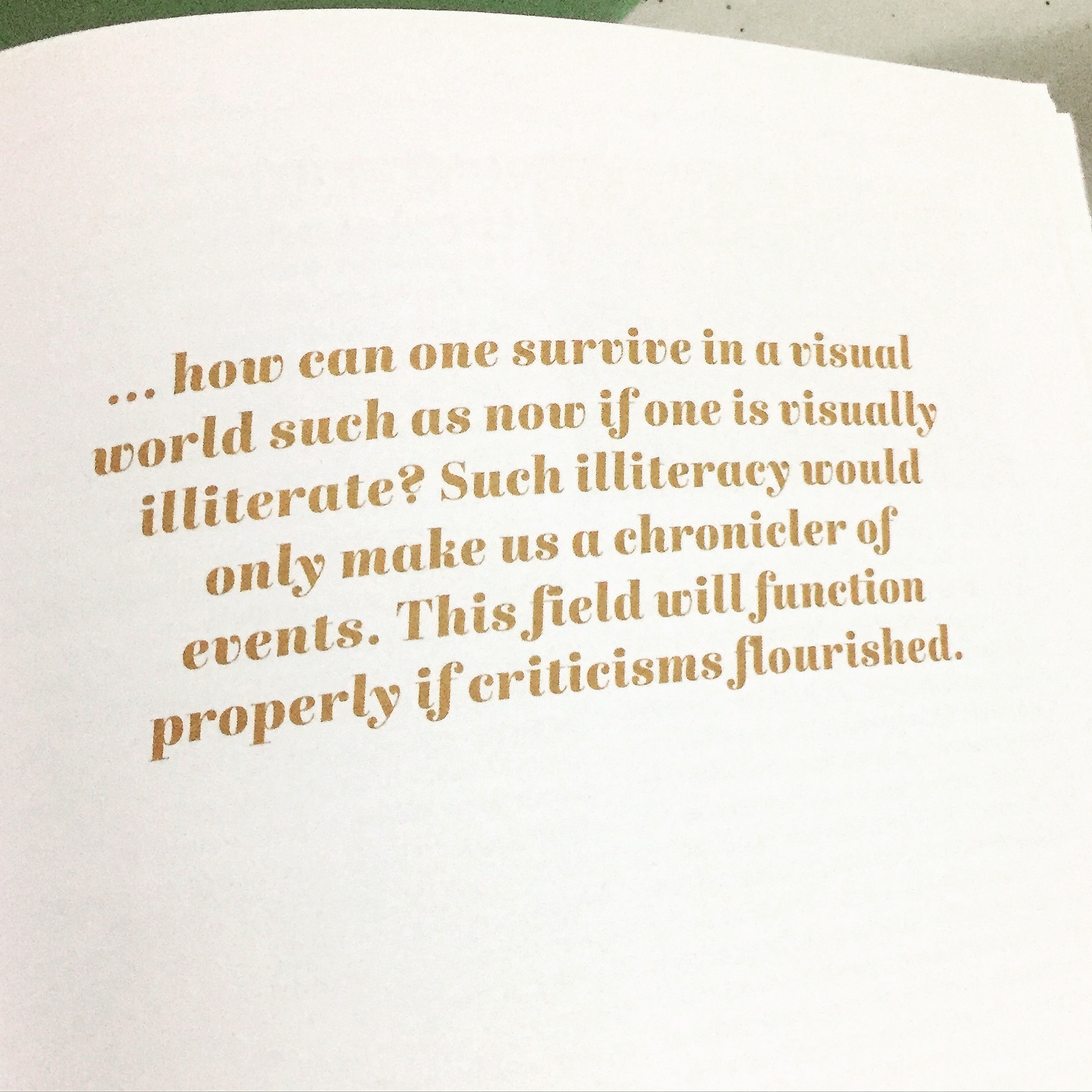

It has become more urgent now to challenge the language and frames that have shaped post-colonial worlds around identity, economics, education, sustainability, and even to question the notion of art itself. What does art in its western concept mean for countries in the global south facing massive inequalities? How are cultural organisations reshaping this discourse through their practise? And importantly how are arts and cultural workers organising and sustaining themselves, so that they not only produce works, but also impact positively in society.

In Yogyakarta, a number of initiatives, including collectives, have developed over the years, many of these working through some of these questions. Interestingly the discussion around "creative economies" is not one of these, despite the challenges of economy. As we will see later in this series, the creative economy as a concept has its limitation, and this is especially so where there is a growing inequality gap.

Politically charged practise has a long tradition, heavily influenced by the punk movement and its DIY approach. Inspired by strong community based ethos, artists in Yogja talk about a DIWO approach — “Doing It with Others”. Socially engaged art making is common in Yogja. Artists here recognise the importance of ones situated reality, working with it and in a connected way with other organisations - a reflection of the concept Bersama Sama (togetherness). In this respect collectivization is both a strategy of survival but also a politically charged act in its own regard. Groups of cultural workers band together and develop a set of positive values rooted in a belief in the importance of symbolism, creativity and expression, as a way to make a positive contribution to society. These form the bedrock of values that guide cultural workers to address what it means to be participant in a change project.

Interesting Case Studies

The following organisations, some of which function formally as collectives, have practises worth looking at further. Each has worked with social justice in some form of the other, and all have been forced to think critically about the frames in which they function, and in how they organise themselves to tackle the their contextual challenges and further their practises.

CEMETI ART HOUSE AND IVAA

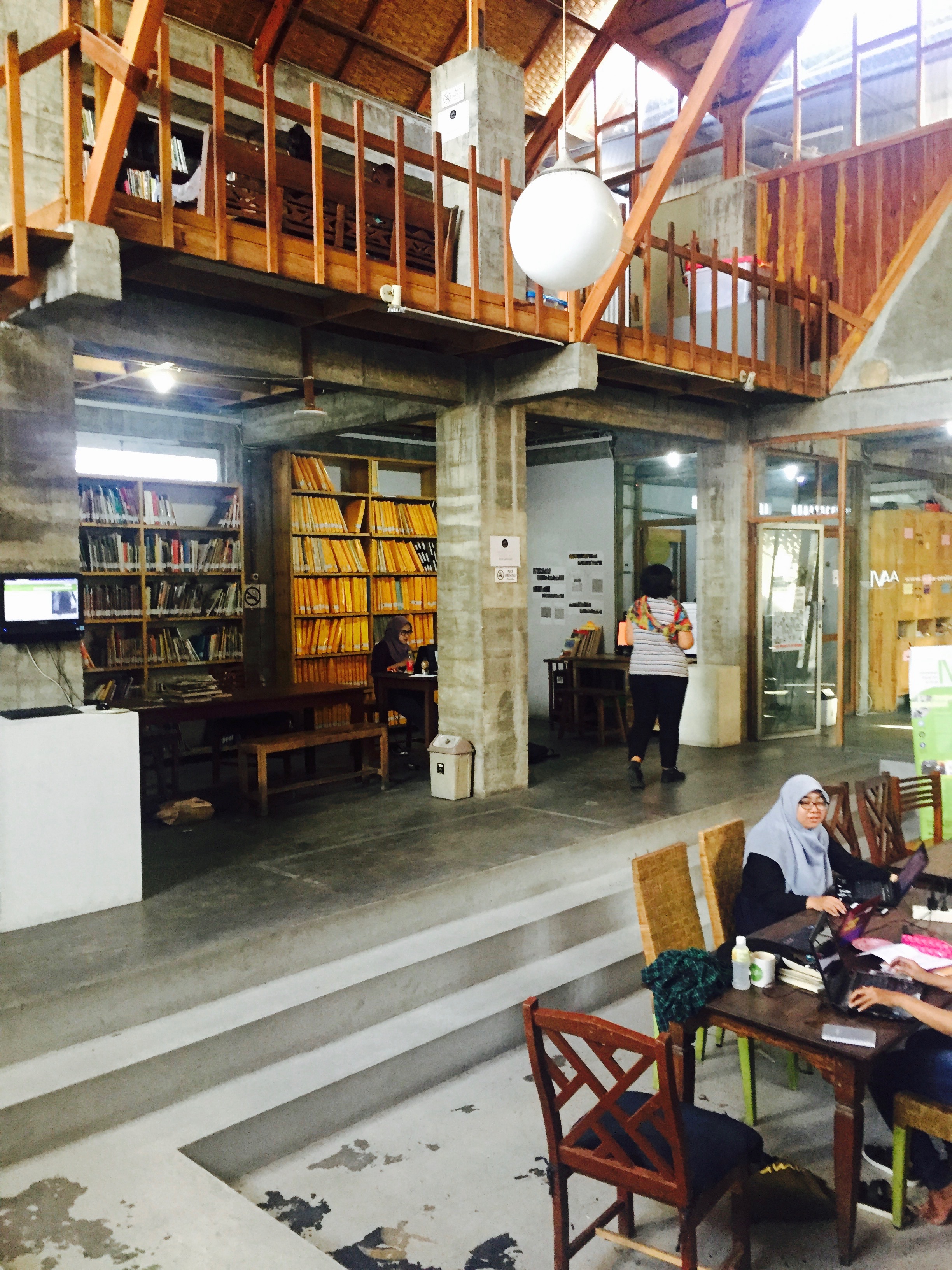

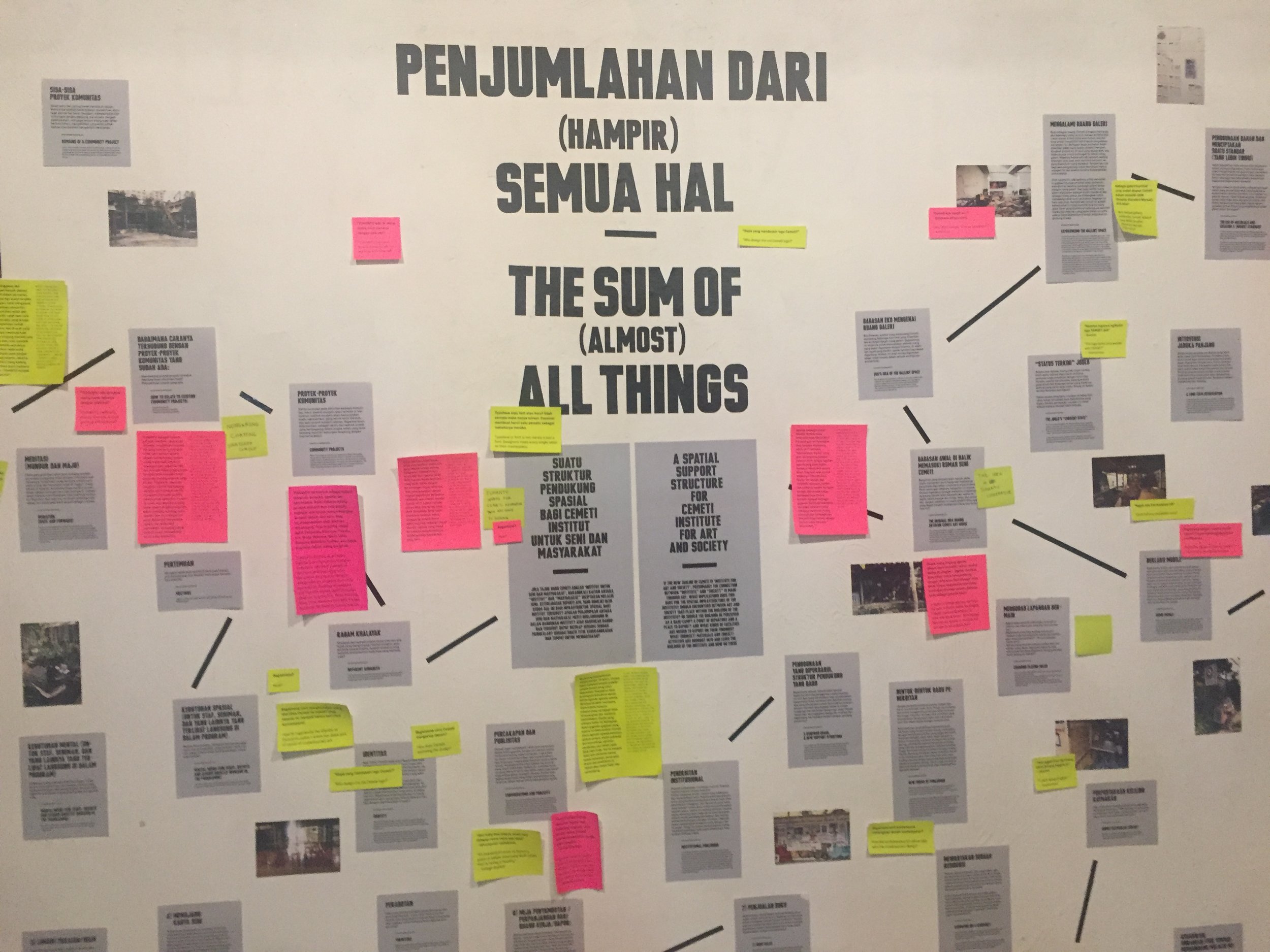

Cemeti Art House is the first contemporary art space to establish in the city. It is an important and seminal hub which has gone through various mutations and is now focused strongly on a residency programme for international and local artists, together with a gallery where innovative non profit projects are displayed. Cemeti, was set up by husband and wife team, Nindityo Adipurnomoand Mella Jaarsma both of whom are artists. Mella in particular has been active in, and key to, a number of processes around cultural development in Yogja, but now focusses more on her artistic work dealing with issues related to race, identity, body and xenophobia. Cemeti was central to the setting up IVAA: The Indonesian Visual Arts Archive, which it provided a physical home to for many years as well as a guiding spirit.

The IVAA is now a separate non profit based in a custom designed space. It has played a key role in documenting the development of visual arts in Indonesia, with a special focus on Java. Besides a collection of over 16 million items — images, documents, sound recordings, it has an excellent on line archive searchable by a host of tags. This is resource available in Bahasa and in English. It hosts a library of publications including a number of literary and art journals produced in Indonesia, but also the broader region. At various times, it has curated its archive in ways that point to its politicized cultural ethos — critically examining it in relation to Body and Gender, Environmental, Creative Industry and Diversity for example. It recognises the challenge of questioning its frames and forms and is busy reconsidering notions of archiving and received notions around visual arts and the construction of history. From this year it will host a archive festival, including talks around such issues of art, democracy and fundamentalism. Artists will be invited to work with the archive in respect to these themes. To bring in broader communities, beyond artists and intellectuals into the festival, it will include performative approaches that involve community engaging with personal histories through their relationships with their own artefacts.

TARING PADI

Taring Padi is a radical collective that started with the ex students of the famed Indonesian Arts Institute, squatting their vacant arts school building after it had shifted premises. This claiming of space took place during the early days of the Reformasi, and the collective lived together in their old school and made radical art. After they were ejected by the state, who set the building up as the Jogja National Museum of Art, they continued their practise in different spaces. The group now owns a modest but beautiful self built studio, living and educational space in a quiet village environment on the outskirts of Yogja. The collective has gone through various iterations, and is now run organically after rejecting an earlier structured collective approach. However it has retained its very strong focus on socially relevant and collaborative art making. As core member Djuwadi has said in a previous interview: “Our mission is to revive “People’s Culture” and to advocate and strategize for a united front supporting democratic and popular change in Indonesia. We try to do this through art being made by and for the people.” Thus it has worked collaboratively with a range of actors: farmers and fishermen on environmental and land rights issues, with trade unionists on workers rights, and with women on issues of feminism. By spending time, living and dialoguing with people, the group surfaces the key themes and issues. Thereafter working with traditional Indonesian forms of art making: woodcuts, puppetry, music amongst, it creates processions for protest. This creates a space, both in the process of making and in the procession, for a rich ongoing dialogue between the participants and others about the issues. It is a much reduced collective now, but is active with individual members making work and projects, which are commissioned or where communities invite the collective in.

RUANG MES56

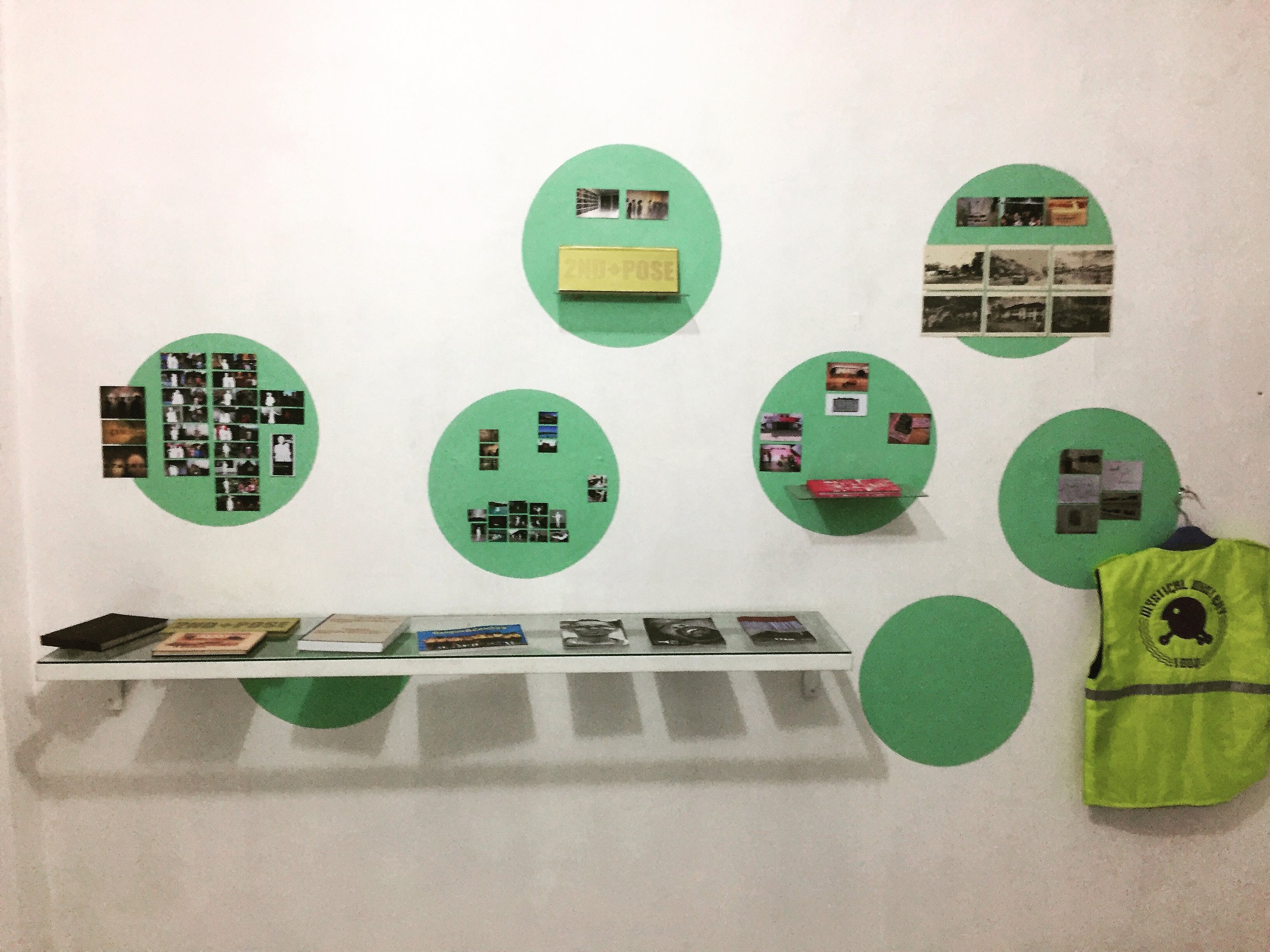

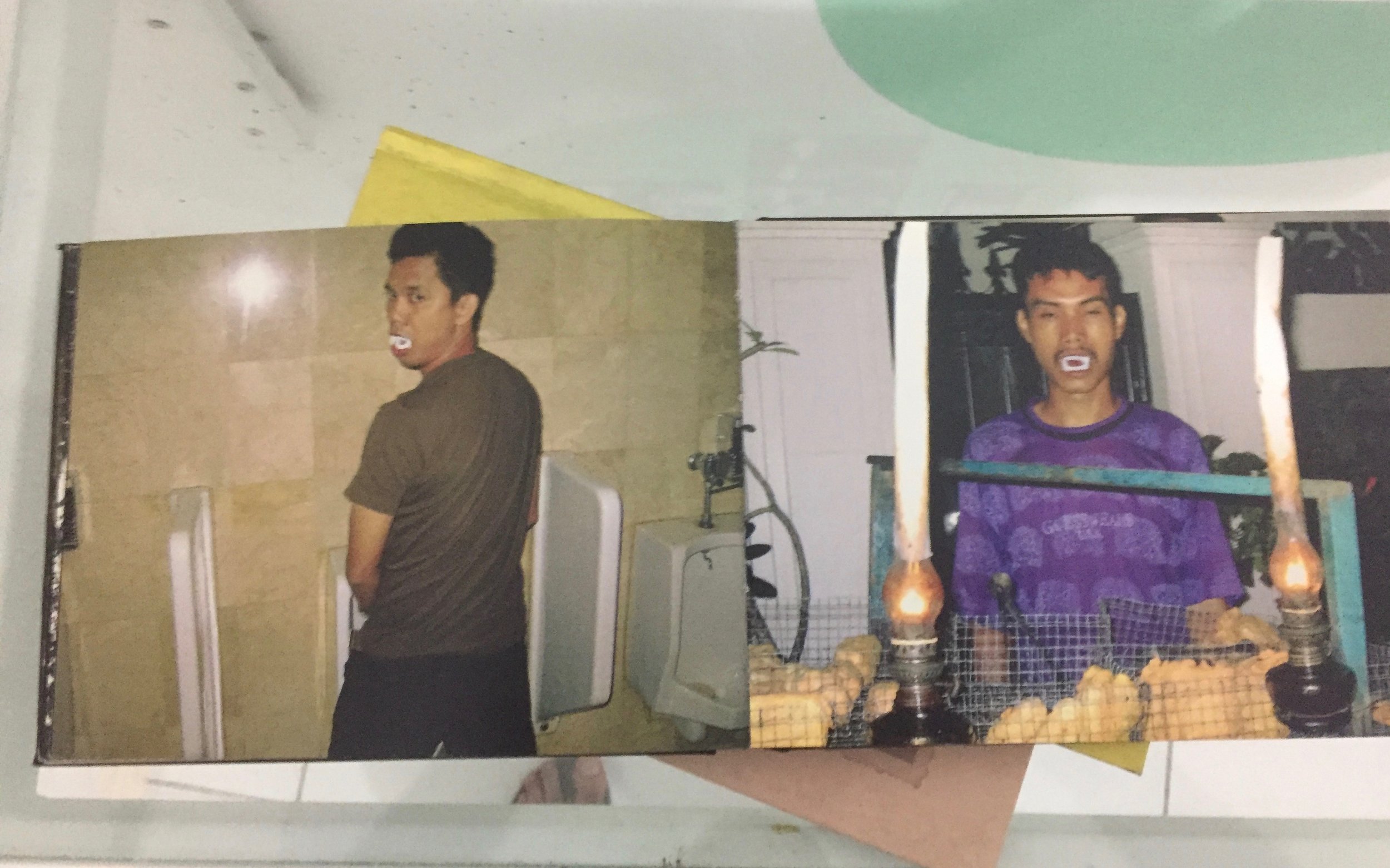

Ruang Mes56 is the oldest photo collective in Yogjakarta and started as Taring Padi did, with art students collectivising. In this case the ex-students rebelled against the narrow definitions of photography they were exposed to through a teaching approach that had primed them instrumentally to either begin work in the commercial sector, news or as social documentary photographers. The collective was interested in art photography and increasingly in political relational practises. Thus the collective began to explore various art photography making approaches and then, as now, produce individual projects and increasingly, since the early 2000s, collective projects. These are often commissions. They happen with art events as with the “Cool and Famous” project that appropriated the tradition of graduation photos of students at the Yogja Biennial. Or the “Alhamdullilah We Made It” project, working with refugees from Afghanistan and Myanmar who were attempting to seek asylum in Australia, which was a commission for the Adelaide Biennial. Alternatively they happen as commissions for aid agencies, such as a project with young children impacted by the earthquake — in this case the artists helped traumatised youth to find an emotional centre by working with personal images about homes, family and friends, and to help revive an enthusiasm about living. Individual artists work broadly with art photography. One of the group Rangga Purbaya, has been working with personal archives related to disappeared individuals from 1965/66, including his own grandfather and memories of survivors and families.

Working with a structured collective management structure, Ruang Mes56 comes across as a relatively slickly run organisation. Its current space which it rents, has a project room talking about its history, a gallery, a shop selling products made by the collective and its individuals, a residency programme, a library, work spaces and a regularly run cinema night. It also has an administrator, allowing the artists to focus on their art making. A number of the original members are still involved actively and there is a cohort of younger people in the collective which has swelled it to 18 active members.

KEDAI KEBUN FORUM

Kedai Kebun Forum responds to a wide network of artists. It was set up to be self sustaining space and has a restaurant, exhibition/shop space, informal work spaces, and a multifunctional performance and events space. This hosts music, performance, exhibitions and even interfaith and same sex marriages. It is owned and led by the dynamic husband and wife team, Agung Kurniawan and Yustina Neni. Agung is a well respected artist working increasingly with performative and relational practises — his projects have engaged with the histories of 65/66 as well as an artists led action to find a new mayor, asking ordinary citizens to stand for election and hosting gatherings to hear manifestos for change. Agung is also the executive director for IVAA, providing a light and more strategic engagement with the organisation. Neni is a chief person behind the Yogja Biennial, amongst others. The Kedai Kebun is the chief forum where the concept for this event (and others) is annually developed through engagements with various artists, bodies and stakeholders. In this way the space becomes a nexus for a number of important cultural initiatives happening in the city.

The Challenges of Organisation: Form and Function.

Although collectivisation is only one of the various organisational forms used in Yogyakarta, as evident above, it is ubiquitous in the city. We will meet others in next weeks piece. Many collectives started with artists actually living together as a group, initially as students. Over time, as the participants mature and find life partners and have children, the collectives become more of a work space. Often the participants are friends, not just people who share common vision - they enjoy hanging out with each other, working through projects. Over time members drop out and new members join as group dynamics change.

Indonesia is a deeply patriarchal and women are often marginalised in decision making. Interestingly this oftentimes plays out in the Indonesian collectives, and many female creatives complain that they often brought in only as administrators, with the artistic elements run by a "boys club" in effect. Collectivisation is no easy task, as this dialogue with Kunci— a independent research unit looking at art and society, also functioning as a collective, shows. Kunci is unusual as it is not composed of art makers, but composed of researchers working with art and creativity. It is also experimenting with a non-hierarchical structure. Leadership is always an issue for collectives - its either one person or a rotating leader, and there is often the concern about how many rules and regulations are needed to maintain the structure before it looses its dynamism in bureaucracy. Kunci has been experimenting with a totally flat structure for a number of years and many of the team feel it is working. However as the dialogue in the linked piece shows, it has its challenges - here a female member consistently raises the mundane task of who will be buying the toilet paper that month, highlighting some of the gendered relationships that inevitably emerge around the everyday.

Collectives seem to work in Yogja, partially because of its urban social history and the indonesian philosophy of Bersama Sama (togetherness), but it is also because it is such a poor city. Collectives are fragile entities due to Yogja's financial challenges, yet these bodies continue nonetheless, with artists pooling resources with the longer terms ends in mind. They're borne out of necessity. Yet as experiments in being together, as spaces of sharing and negotiation, they help the artists involved to hone an empathetic social consciousness. This in turn impacts on how projects are developed and delivered with a relational edge.

Coming next

In the next piece, we discover more about Kunci's work with schooling and two other collectives, both of which have a strong emphasis on youth and popular culture.