A Bandung Heritage: the Afro-Asia Conference 1955

Last week we experienced Bandung as a Creative City, but it has great relevance as a defining moment for the history of global south cooperation... for one highly esteemed moment in time.

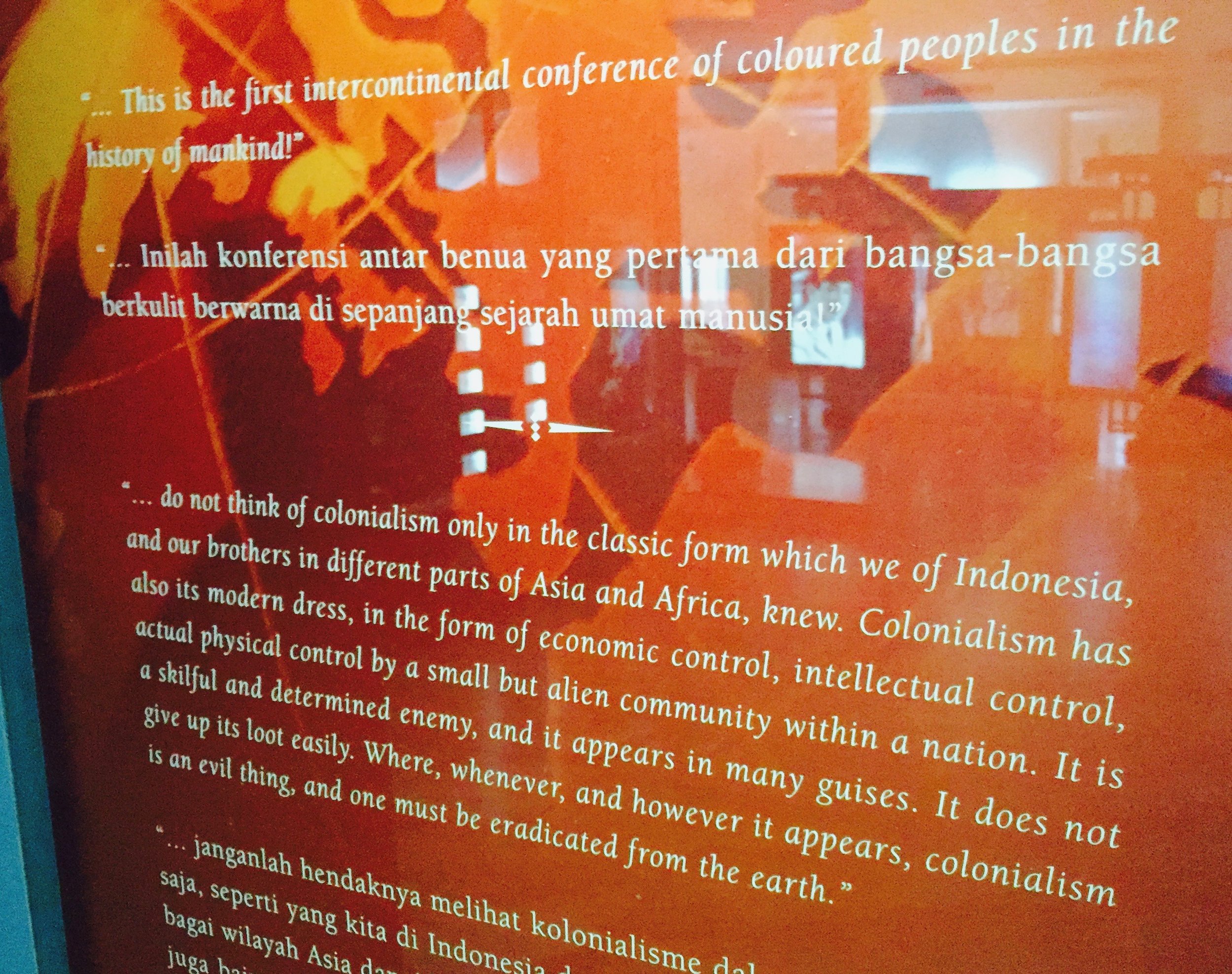

The Afro Asian Conference held in the city of Bandung April 18–24, 1955 was the first major meeting of heads of states of countries which had(bar one) recently achieved independence from colonialism. It was the biggest international meeting of people of color ever held at that point, and the significance of the event was not lost on anyone who attended, nor has it been lost on Bandung itself. The venue where the conference was held has been memorialised as a museum with a library attached dedicated to collecting material relevant to the issues covered by the event. Annually its memory is celebrated by a carnival. But is this enough of a recognition for such a momentous event? Are there alternatives?

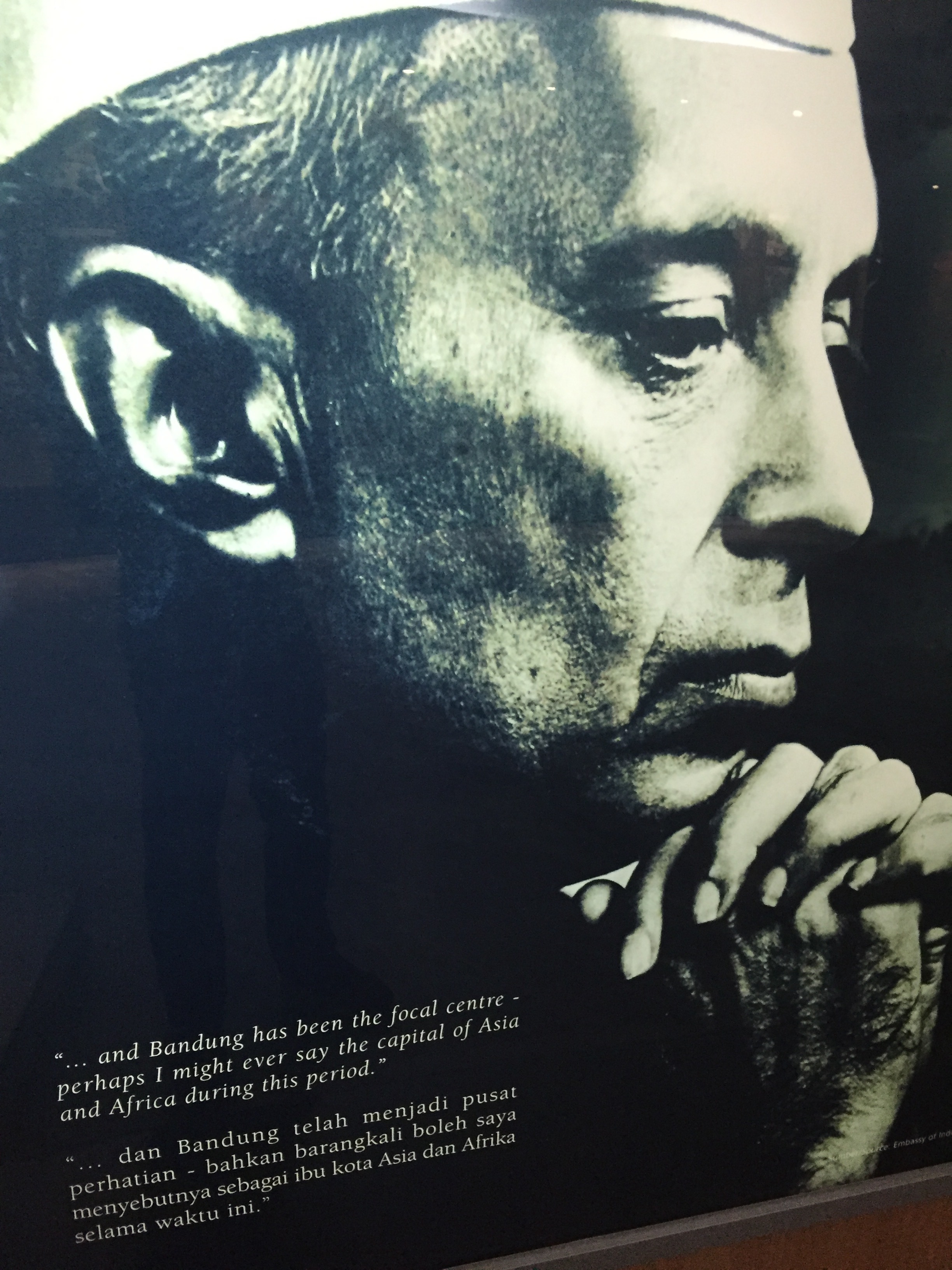

The Bandung Conference as the event is more popularly known, was hosted by the Indonesian government, under the leadership of its president Soekarno, and organised jointly with Burma, Pakistan, Ceylon (Shri Lanka) and India. The 29 independent countries who attended represented 54% of the earths population at the time (around 1.5 Billion people). The conference was held to explore Asian economic and cultural co-operation and was a show of solidarity at a time when many other countries were still under the yoke of colonial domination, locked in bitter struggles for their freedom. Thus colonialism, racism, and neocolonialism were key areas of debate.

Out of the dialogues attended by key leaders who were already icons in the world, came the inspiring and unanimously accepted Bandung Declaration.

The Bandung Declaration on a plaque along the street between the conference venue and hotel

The Bandung Declaration

The10-point declaration is significant for its idealistic promotion of world peace and cooperation and its response to racism. It states the following:

- Respect for fundamental human rights and for the purposes and principles of the charter of the United Nations

- Respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nations

- Recognition of the equality of all races and of the equality of all nations large and small

- Abstention from intervention or interference in the internal affairs of another country

- Respect for the right of each nation to defend itself, singly or collectively, in conformity with the charter of the United Nations

- (a) Abstention from the use of arrangements of collective defence to serve any particular interests of the big powers

(b) Abstention by any country from exerting pressures on other countries - Refraining from acts or threats of aggression or the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any country

- Settlement of all international disputes by peaceful means, such as negotiation, conciliation, arbitration or judicial settlement as well as other peaceful means of the parties own choice, in conformity with the charter of the United Nations

- Promotion of mutual interests and cooperation

- Respect for justice and international obligation.

In addition to the declaration, the event dealt with a number of tangible issues related to technical support and a commitment for exchange of knowledge

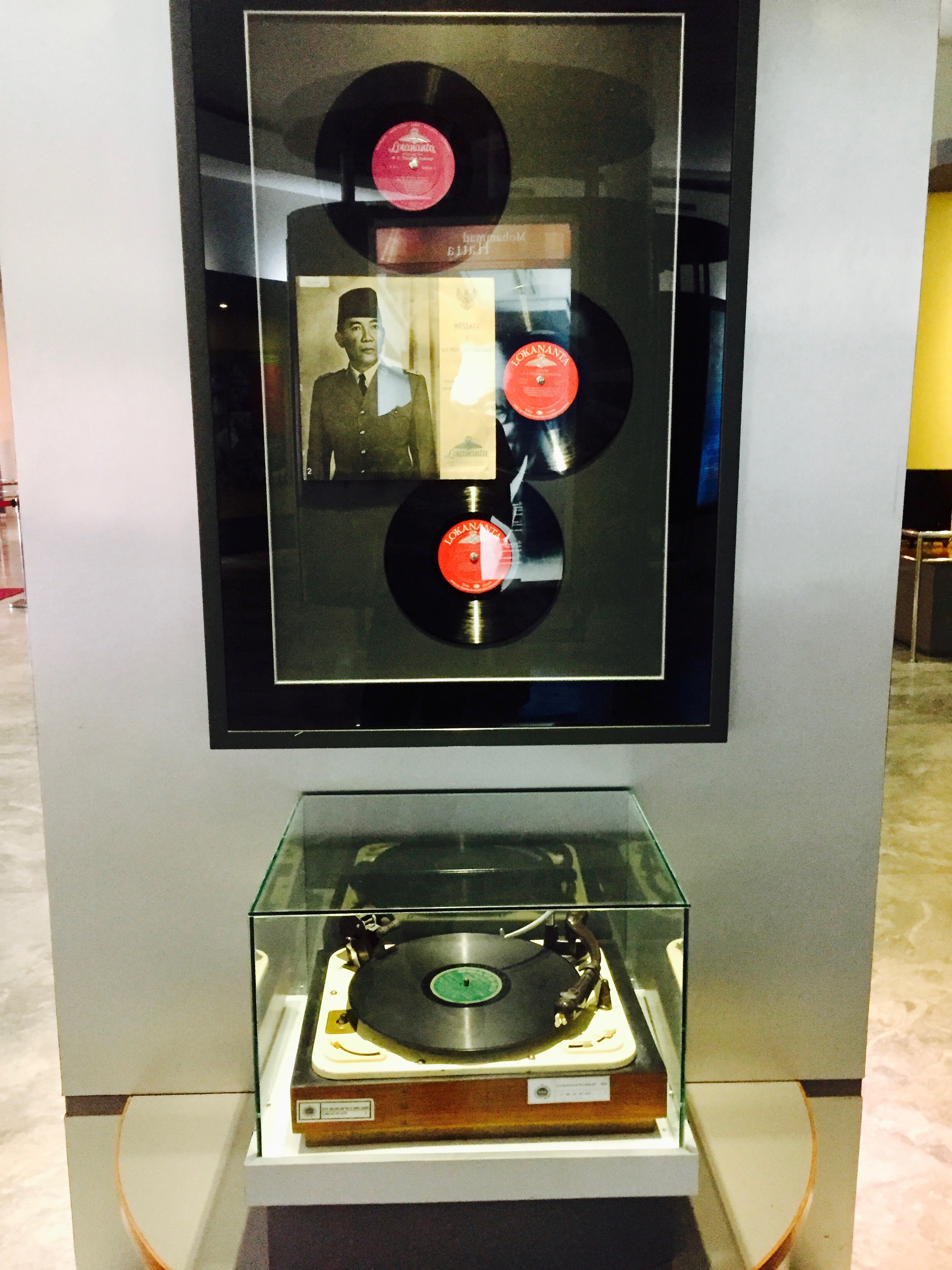

A Cultural Landmark, Memorialised in Bandung

The conference venue

The Bandung Conference was attended not only by political leaders, many of them icons of the independence struggles of their respective countries, but also a number of artists and important cultural figures. One of these, a famous african american writer, Richard Wright wrote the acclaimed book The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference,in part a travelogue chronicling his meetings with Indonesian intellectuals and cultural leaders. It remains one of the more important documents of the time other than the museum itself. In it Wright recognizes and celebrates the significance of the event and reflects on his own experiences as a person of color, regarded as a lesser human being in his own country. Moreover he reflects on the crippling internalized lack of confidence people of color were saddled with, and especially their sense of self when confronted by their white colonisers, the impact of years of subjugation. Thus it was significant that race was such a central issue of dialogue at the event. A dialogue that is still so relevant today.

The museum, is based in the beautiful art deco building the Gedung Merdeka and is well managed by the Indonesian Foreign affairs department. It is free for visitors, who are eagerly led around by guides and has a comprehensive exhibition with artefacts and copies of publications on display. The final moment is a visit to the great hall where the event was held. One can also spend time in the library and there is also ascreening room (which was curiously showing a Hollywood film during my visit). It is an important space and one of the few museums available in this large city.

The route from the Art deco hotel a short walk from the Gedung Merdeka, where most delegates stayed is also memorialised with plaques and flags. It is celebrated annually as part of the city's commitment to the Unesco Creative Cities programme in a Afro Asian carnival. There have been a number of anniversaries for the event, attended by world leaders, including South Africa's Thabo Mbeki and its past president Nelson Mandela, with functions held in Jakarta and at the memorial site.

The Legacy of the Event

The late 50s and the 60s was a historic time for the previously colonized world. Many had endured centuries of pillage during which their populations had been turned into third class citizens, hard battles had been fought for Independence. Within a short period after the Bandung conference many other colonial countries, including the Latin American and Caribbean ones, achieved their independence, some would take longer. It would be almost 4 decades later that the final "colonised" country (also a subject of debate at the event) South Africa, would achieve its moment of liberation

The hotel the conference delegates stayed in

Importantly, the event would mark the start of the Non Aligned Movement, which was a reflection of the various countries commitment (at the time) not be aligned to any of the key cold war nations. The use term the "Third World" arose out of these developments.

The United States was one of the more significant countries unhappy with the conference because of its fears around communism. The conference was attended by a number of key countries flirting with socialist idea and Communist China was a major player at the conference. The USA had just come out of the Korean war and by the end of the year would have started a defining war with one of the delegate countries - Vietnam. As the key neo colonial state, the USA would be complicit in a number of actions of destablisation amongst countries involved with the Bandung Conference, including Indonesia, and a number of African and Latin American countries in the years to follow.

It was partially this de-stablisation by the USA, and the ongoing controlling influence by previous colonial masters that would mar the potentialities of the countries who had emerged out of this time. The possibilities from all reports were clearly and apparently felt and voiced at this important event. But many of the countries imploded from within: corruption, mismanagement and power hungry leaders would continue to let down its citizens in the decades to come. Many of the countries in the non aligned movement would end up aligning to one or other of superpowers, and despite the commitment to not attack each other, a number of brutal wars were fought. A few of the Bandung Conference delegates (most notably Indonesia) and a number of non aligned movement members would end up becoming dictatorships, committing the kinds of human rights violations they had pledged never to do. Many of these self same individuals have served as chairs of the body and its legacy is thus a tarnished one The various spin offs have themselves been less than promising.

a publication emanating from the conference

Conclusion

Despite these disappointments, it is important to remember the idealism and hope that came out of the important Bandung Conference. Many of the countries who have come out of the time have gone on to find new, often innovative ways of responding to the impacts of colonialism.

Moreover the sentiments and commitments of Banding Declaration were clearly heartfelt, even though a number of its lofty aims were corrupted. Many citizens of these countries (and others who later claimed freedom) would be inspired by what some of their leaders articulated at this auspicious moment. For these reasons its important to remember the event for what it tried to do, for its impact in bringing an important grouping of countries together to address common concerns, for trying to say and do the right things at a critical period in history.

Then of course there are deeper questions about boundaries themselves: both artificial ones set by the departing colonial rulers and those hard fought for by ultranationalist. And its worth think of what these boundaries mean in the context of human development and suffering, what they could may mean if reconsidered, with a deeper sense of the principles guiding the architects of the Bandung Declaration? What sort of world is possible if the postcolonial was reimagined beyond the fictional limitations of post world war 2?

Perhaps its time for a re-visiting of the Bandung Conference and a reconsidering of its importance in fostering the first great moment for south-south dialogue and exchange, not from a political, but from a cultural and a humanist perspective. It may be an opportunity for the City of Bandung to consider its creative city title beyond an annual performance of remembrance, and play a facilitative role in bringing real meaning to this important global south heritage. Could the City move from designer/architect to designer/facilitator? What could the role of artists, creatives and cultural workers be in reshaping the dialogue, started in 1955, for a 21st century world so badly in need of moments of creative transformation?