Opening the Doors of Culture

Street art in Observatory, Cape Town, October 2018 (outside the Drawing Room Cafe)

The Doors Of Learning And Of Culture Shall Be Opened!

The Freedom Charter, Congress of the People, Kliptown, South Africa, on 26 June 1955

What do people want from a cultural policy? How does government turn peoples needs into actionable steps that can be monitored? One of the objectives of this website is to make Cultural Policy more accessible to the average person. I am interested in having publics recognise policy as a contract between government and its citizens – it must lay out how government will allocate tax revenues and align the work of its public servants to meet the key demands of its people. Just as in any contract, the responsibilities of the contracting parties and more especially, the key purpose of the contract, must be clear.

I decided to check. Given a narrow choice what would people identify as the most important thing a cultural policy should do? Could this help assess where the gaps are currently? Towards this end, I tried a very crude experiment on social media, asking my extensive facebook friends list in South Africa to make a choice one way or the other, whether they wanted "a cultural policy that a) enabled the majority of people the opportunity to be involved in cultural activity of their choice, close to where they could have regular free access OR b) access to experiencing culture determined by a small group of experts in a limited set of centralised places at a small fee". Although there were some complaints about the absolute binary nature of the question, and those who pointed out that my framing does not make the second an attractive option, there was an overwhelming response from the majority of people for the first option. A number of these were people involved professionally in the arts and heritage environment, but the majority was not.

Obviously, firstly this was far from a scientific way of getting answers, and secondly there is a need for both aspects, and clearly a number of the audience were aware of it. It costs money to look after the heritage of a country for example, and access to presented work by artists honed in their craft is vital. But as I figured, reflecting on the South Africa's journey in the development of its cultural policy (from the Freedom Charter to the first White Paper on Arts and Culture), that latter was missing its mark for the majority of its citizens. People do know what they want and they know why - they recognise that investing in fostering human creativity is something that brings with it a great deal of positive spinoffs for communities. This interest in "cultural democracy" has a global relevance.

Changes in the notion of Culture

publicity image from Inktober 2014

In the last two decades the internet and smart phones have really changed the ways in which people have consumed content, and has increasingly made people producers of their own content. Some of this content is digital, like the vast number of short videos, photographs and music made. Others are analogue, the end results shared digitally - like the over 3 million Instagram posts of drawings for the #Inktober2018 project which fosters drawing as a creative outlet, open to everyone (while changing the notion of what a festival could be). Blogging has continued to grow and more people are reading and commenting on blogs. Increasingly people are living their lives online, sharing and commenting on content. Obviously there is a great deal of problematic material, toxic comments especially, but there is also a great deal of camaraderie and empowerment amongst sharing communities. But the amount of content coming from the global South is poor, as we have seen with the recent UNESCO Report on the Convention for Cultural Diversity. This is despite the very high level of smart phone access, especially since the introduction of cheaper handsets..

Secondly there is a growing movement around maker spaces, and an ongoing interest in individual and collective creativity, whether it is singing, knitting, pottery or more. Much of this can be described as everyday creativity, with participants not interested in making product for sale necessarily, nor is it about them becoming professional artists. Creating here is simply for the enjoyment of making things, and often an opportunity for human connection in a world that is increasingly alienating.

This, especially the second, has a strong connection to an older cultural policy idea: cultural democracy

Cultural Democracy

"As an ongoing process, sustained by, and in turn sustaining, human creativity, cultural democracy is not to be understood as some utopian’ end’, but rather as an on-going ‘means’ of fostering self-actualisation through mutuality. The benefits of cultural democracy are potentially very wide ranging indeed, being experienced across arts and culture, education, creativity, industry, health, wellbeing and fulfilment and impacting individuals, organisations and communities in many different ways (including self-expression, recognition, voice, transferrable skills, career development, friendship and community). Crucially, by highlighting possibilities as well as outcomes cultural democracy promises to make a real and positive difference for everyone, from playground to pension." Towards Cultural Democracy, Wilson et al 2017.

Cultural democracy has re-emerged recently in the work of cultural policy thinkers and researchers in the Global North (articles by Matarasso and others document this well). The roots of Cultural Democracy as a cultural policy concept emerged around the late 50s- 60s. The world went through some its most important contemporary moments including the rise of social movements - the liberation struggle of previously colonised countries, and the civil rights, the second women's rights, the gay rights and the indigenous peoples rights movements, all furthered collective thinking for a better more ethical world. Later, technological shifts led to greater access to equipment for the mass production of cultural products, leading to cheaper and more portable stills and video cameras, cheaper recording facilities and quicker and cheaper ways to distribute content. All of these happened as people were questioning such ideologically loaded notions such as "high" and “popular” culture and thus the very definition of culture. This was thus a highly political time and there was a strong focus on democratic and participatory practices and of everyday culture.

This spawned many radical cultural policy shifts including support for the growing community arts movement that advocated for access by all to the culture of their choosing. In various global North cities, citizens began demanding community arts centres for access to the means of production and for workshops. The role of the artist as a facilitator and a focus on process emerged. This sparked a period of state support. But this was slowly chipped away from the late 80s onwards as neo-liberal economics and austerity became the order of the day. There was an increased focus on creative industries and the entrepreneurialisation of the arts, which has continued into today. The end result is that the public benefit opportunities which access to culture provides, have been substantially reduced to the detriment of communities and their empowerment.

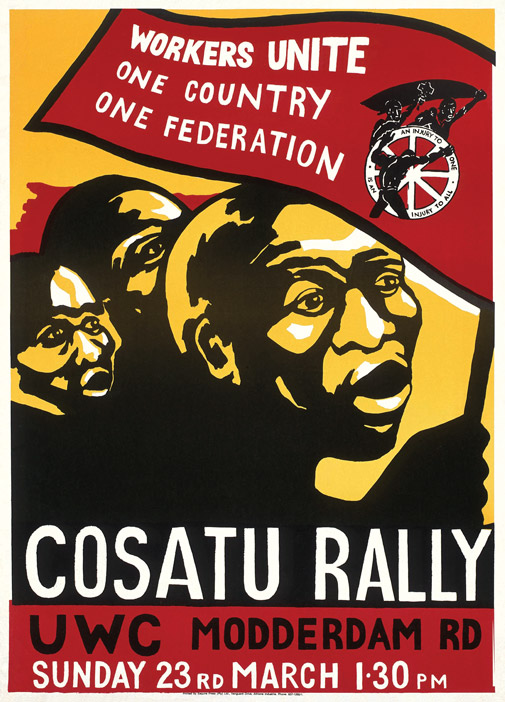

From the Community Arts Project archives. (University o f Western Cape).

Cultural Democracy in South Africa

Ideas around cultural democracy were strong in the South African context too, as I have covered in a range of previous articles. A number of projects emerged in the late 70s influenced by these global shifts. However it was the Gaborone Culture and Resistance Conference and Festival (1982) which made the key impact. This was the first, and most significant, national gathering of South African artists, cultural and media workers, during the Anti-Apartheid struggle. It attracted most key players in culture from inside the country and those in exile, including such luminaries as Hugh Masekela, Abdullah Ibrahim and Robyn Orlin, to name a few. The programme included a conference, exhibitions, arts workshops, and performances, with a high emphasis being placed on knowledge sharing. Organised by the ANC's ‘Medu’ Arts Collective, it was overtly political. It advocated the use of art towards the ends of social change, and propagated a set of practices that would dominate the South African struggle context over the next decade. These ideas built on principles governing traditional art that focused on functionality and community relevance. As a result, post-Gaborone, the visual aesthetic around the struggle was sharpened at protests and gatherings and in the international media. The use of screen-printing and documentary photography, a more layered struggle theatre incorporating mixed media, music and dance, and the explosion of arts collectives and networks can be traced back to this seminal platform. A number of "community arts projects" emerged out of this moment and furthered ongoing thinking about the artist as a "Cultural Worker" and of "Peoples Culture" . But much of the successes of this time were lost post the democratic change in 1994.

Implementing The New SA Cultural Policy

Bill of Rights of the SA Constitution

Everyone has the right to freedom of expression, which includes ... freedom of artistic creativity ... (paragraph 16)

Everyone has the right to use the language and to participate in the cultural life of their choice ... (paragraph 30)

The Freedom Park initiative in Tshwane (pic from Brand South Africa website)

In text, South Africa's cultural policy (the White paper on Arts and Culture 1996) appears to be influenced by and speaks to much of the language of cultural democracy. But its implementation post ‘94 was heavily influenced by advocacy from a powerful lobby of artists and arts disciplines that demanded a de-politicised dispensation (the National Arts Coalition) . Artists are vocal and demanding but their activism, here as elsewhere, (bar a smaller group of activists) is often limited to demands for funding (the black hole of arts funding as some would call it) . The overemphasis on funding in policy debates, instead of on discourses such as cultural democracy, prevents other, less artist focussed, approaches to working with culture emerging. Moreover government has embarked on a number of expensive and ultimately elite centralised projects to further a particular ruling party vision of a future South Africa. A project like Freedom Park for example is a costly exercise and its impact, beyond its regional reach, is questionable.

South Africa has "the most developed policy framework and largest reservoir of publicly available finance for culture on the continent" suggests cultural manager and researcher Joseph Gaylard, but raises concerns about how the budget is actually spent. His research looks at the Department of Arts and Culture's (DAC) budget of almost R4bn ($278,4m) in 2017, and recognises a heavy slanted towards centralised institutions. Heritage and Performing Arts bodies (who receive 29% of the budget) are based in areas inaccessible to the masses. Most have "outreach" projects for this end, determined by the institutions themselves. Many of the institutions are underfunded (or some would say overly top heavy) these are forced to find additional money from a limited range of sources for outreach. As a result there are only a few projects that engage with broader communities and little space for bottom up approaches.

The South African Dept of Arts and Culture Budget 2017. Adjusted presentation slide from Joseph Gaylard presented at the SACO conference (2018). Figures in ZAR in thousands. ( R14.55 to a $ on 25 Oct 2018)

Bottom up ?

"Community Arts Centres" received significantly less than 0.3% of the DAC budget in 2017, and for some years previously received nothing at all. But community arts centres are a misnomer. There are few actual centres, since many closed a few years back. Many of the initiatives receiving money now are not the kinds projects of a cultural democracy nature described above. They are simply arts projects based in marginalised communities and receive the crumbs from a "discretionary" budget (identified as cultural and creative industries). The bulk of this discretionary budget (9% of the total) is spent on a range of initiatives including the Mzansi Golden Economy, ringfenced budgets for the classical arts, as well as vanity initiatives determined by the DAC.

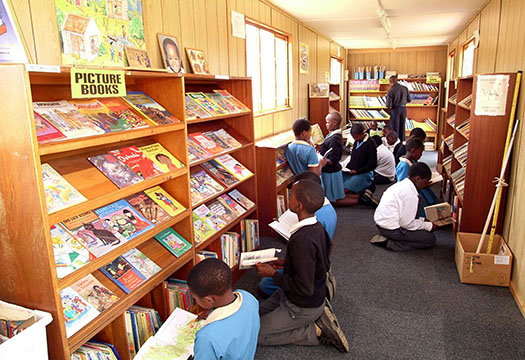

A library in South Africa (pic from National Libraries website)

On the plus side a whopping 35% is allocated to libraries, this budget of R1,3bn is distributed throughout the country via municipalities. At the end of the day it’s a modest budget by the time its distributed to each library, but it is probably the closet South Africans get to see tax money in their neighborhood. Moreover there are some excellent librarians, some of whom push their often modest facilities to the limit to allow a broader range of activities than simply the provision of books and ICT access. This includes working with arts and heritage projects. Some (emerging) research also shows that libraries are important safe spaces for young people and women, this is especially important to recognise in crime-ridden South Africa. But libraries have a range of constraints (limited opening hours, lack of space, lack expertise beyond librarianship amongst others), but a number do have community support committees ("Friends of…"), which enable them to raise additional budget. However much more could happen including guidelines and financial support to broaden their work to bring the kind of cultural democratic work to the fore. The challenge though is the lack of understanding of culture at a municipal level and the reticence of local government to allow a broader scope of work to happen.

As we have seen in earlier pieces, local government in South Africa has yet to come to the table on culture because it is not their constitutional competency and only a handful of municipalities have cultural departments or budgets. Those that do have such programmes also prefer to fund centralised institutions and very little if any goes to projects on the ground. Few cultural centres in neighborhoods exist, and there are no policy guidelines in place that could enable a cultural democracy approach.

Our Workshop - a maker space set up by Heath Nash at the Guga S’Thebe Arts Centre in Langa (photo from the internet)

What does this all mean?

If South Africans do want a more bottom up approach to culture, something that’s part of neighborhood and that’s accessible, they are going to have to be more demanding about it. If advocacy is left to the general artists and museum workers, its going to end up being a narrower elite focused exercise - Its going to center on the demands of arts groupings for resources rather than on the needs of local communities. But to do effective advocacy more research is needed on budget allocations and staff responsibilities (at all levels of government), to understand the gap between the rhetoric of the state and its actual implementation. Advocacy can also be done with boards of museums and playhouses, who have a great deal of autonomy and set their own policies and guidelines. to argue that they provide programmes more aligned to cultural democracy.

Better research on alternative models are needed with opportunities created to test these out. This may mean engaged research with universities playing a role in running projects as testing grounds. Alternatively there is space for at least one non-profit, or better still a focussed network of parties and entities sharing a clear vision, that can help further more emergent practices, providing possibilities as well as doing research.

While a community arts center in every community may be a preferred outcome, its far from realizable in the foreseeable future. It is useful revisiting national government's failed attempt at providing community arts centres in the late 90s and to understand why two decades later there has been little shift. This may also provide data for doing things differently with local government, at more modest scale and more innovatively. It would certainly help to have at least some community arts centres servicing a few neighborhoods, where these are placed and how they programmme could place an important role in bridging racialised divides.

Lastly libraries could be looked at differently. Internationally many libraries are starting to experiment with adding maker spaces or creative hubs to their offerings. There may be opportunities for communities to start a "Friends of" and help their local libraries to grow their offerings, to become hubs for programmes that could spill over into community halls. Further, recognising that libraries also provide access, albeit at a limited level to wifi access (which is prohibitively expensive in SA) and some have computer stations, creates the possibility to consider libraries as "creative hubs" where young people are taught how to use smart phones better to create and distribute new content. These include how to take better pictures, short videos and more, but to also be trained on how to get the best out of the internet as a tool. It may be difficult for librarians to become teachers of such content, but there is scope for online courses to be provided for such ends, with students getting feedback from other younger people who are skilled - thus libraries can become important spaces to further peer-to-peer learning. This speaks well to the proposals of UNESCO's Convention on Cultural Diversity 2018.

A library in South Africa (pic from National Libraries website)

Why does it matter?

If we South Africans want to have a better society, it’s going to be important for us to use our agency. If academics don't research it, if leaders of cultural and arts bodies don’t question, if people don't talk about it and advocate, and government doesn't engage then the kinds of shifts in cultural policy wanted will not happen. Such a shift should further democratic practices, allow us to connect with each other, help create content about our past, about who we are now and about who we would like to be in the future. In the words of those who responded to my FB "survey" - This will, amongst others "lead to an explosion of even more amazingness." (Theresa Smith); make "culture much richer across the board (Ingrid Kopp); allow "us to explore a broader understanding of what culture does and can do for multiple publics, versus what culture can be engineered to do for a homogenous public that does not necessarily exist in reality," (Karen Ijumba) and help people especially teens …[to]… have a space to express themselves and explore their talents. And… bring people together across all those artificial divides" (June Knight) …and much more.