Memorials and Reconciliation in Cape Town

The Guguletu Seven Memorial designed by Donovan Ward. Photo by Bruce Sutherland

In this weeks piece, we focus on the memorialization of "hidden histories", looking at projects that respond to Cape Town's apartheid and colonial pasts. This builds on a previous piece introducing the concept of memorialsiation and its role as a tool for dialogue.

Why Cape Town needs to work with Memory

The Dirkie Uys Voortrekker Memorial in Cape Town

Cape Town is a city with a complex colonial history, as we have seen in earlier posts. Initially peopled by the indigenous San, and later the Khoi, it was occupied by the Dutch from 1652, and then taken by the British - both of the latter two used it as a base for trade to the East. Later it an important when diamonds were discovered around Kimberley in 1867, prompting a mass influx of prospectors through the city's port. It served as the capital for the Cape Colony and then the legislative capital under the Union of South and the Republic of South Africa. Slavery played a significant role in the history of the city and is the reason the city has such as diverse population, with slaves coming from all over, more especially Indonesia, Angola, and Mozambique. Slaves and their descendants made up two thirds of the population by the time slavery was abolished in 1834. Black settlers from the East and the North East of the country were often restricted from entry into the region. The National Party came to power in 1948 and cemented its hold on the country, instituting a policy of Apartheid, which built on earlier laws of repression. Oppression intensified from the 1950s onwards with the Group Areas Act and other related laws. This led to widespread forced removals which shaped the Apartheid City, resulting in the racialized geography that remains the roots of the city's major problems today.

But Cape Town was also a site of resistance and has a long history associated with struggles for freedom and recognition by the enslaved and the oppressed. How is this story told? Who tells it? How is it used to build social cohesiveness?

Memorials as a Tool for healing and reconciliation?

As a result of the long colonial rule, the city is littered with numerous monuments (well over 200) that commemorate any number of colonial histories, as well as some Apartheid linked ones. But it was only in the early 2000s that memorials were built to recognise the histories of those excluded from the landscape. Dialogue about the cities history and its relation to current social relations has been poor. Much of the alternative story till then (and now) has been told by the District Six Museum, formed in 1994, as an independent space, and which has received little government support over the years. The Memory Project formed in 2005 (after two years behind the scenes work) was an important and short lived attempt to engage the city to recognise its pasts. It had a number of dialogue sessions and resulted in three monuments being built: one in a black "township" - The Guguletu Seven Memorial (designed by Donovan Ward) and two in Athlone - The Trojan Horse Massacre Memorial (by ACG Architects) and the Waterwich and Williams Memorial (designed by Egon Tania) - pictured below. All three pieces remember specific individuals murdered by the Apartheid regime.

The Memory Project was established as a partnership with the City of Cape Town (under the ANC Mayor Nomaindia Mfeketo), The Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (IJR) and was led by journalist and former activist Zubeida Jaffer. It consciously saw its role as a continuation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission - understanding itself as an attempt to draw on memory as a way to heal the city in a participatory process with its citizens. The project started with much enthusiasm and public engagement, although it was, predictably, largely people of color who engaged. This was a continuing thorn of contention in the various talk sessions. Understandably earlier meetings were about the pain inflicted by the past - talking was catharsis for many. However with white people consistently and largely absent in these forums, this led to questions about whether white people were "seriously interested in reconciliation". The latter has been a continuing dialogue amongst the South African public, especially on social media and on talk shows, usually emerging after ever increasing moments of racism, followed by more racist responses in posts and tweets. In 2006, local government elections in Cape Town were won by the centrist party Democratic Alliance. Shortly after, funding for the Memory Project ceased, its champion within the city left and the IJR attempted to, but could not continue with the initiative without resources or political support.

Activating Monuments?

The three monuments built during the Memory Project show that simply building monuments aren't an end in themselves. The two monuments in Athlone are in areas which are thoroughfares, not destinations. There is little information on them on the net. They are often vandalised - the statue by Tania, in particular often has bits of its valuable metal cut off. They are only occasionally visited by the odd tour group, that often focus on "township" tourism or niche tours about the city's apartheid and struggle history. The Guguleu Seven is in a much more publicly used space, and is visited more often by tours, but it too has often been regularly vandalised. Sadly few local people who pass by know about the reason for the pieces or what they represent.

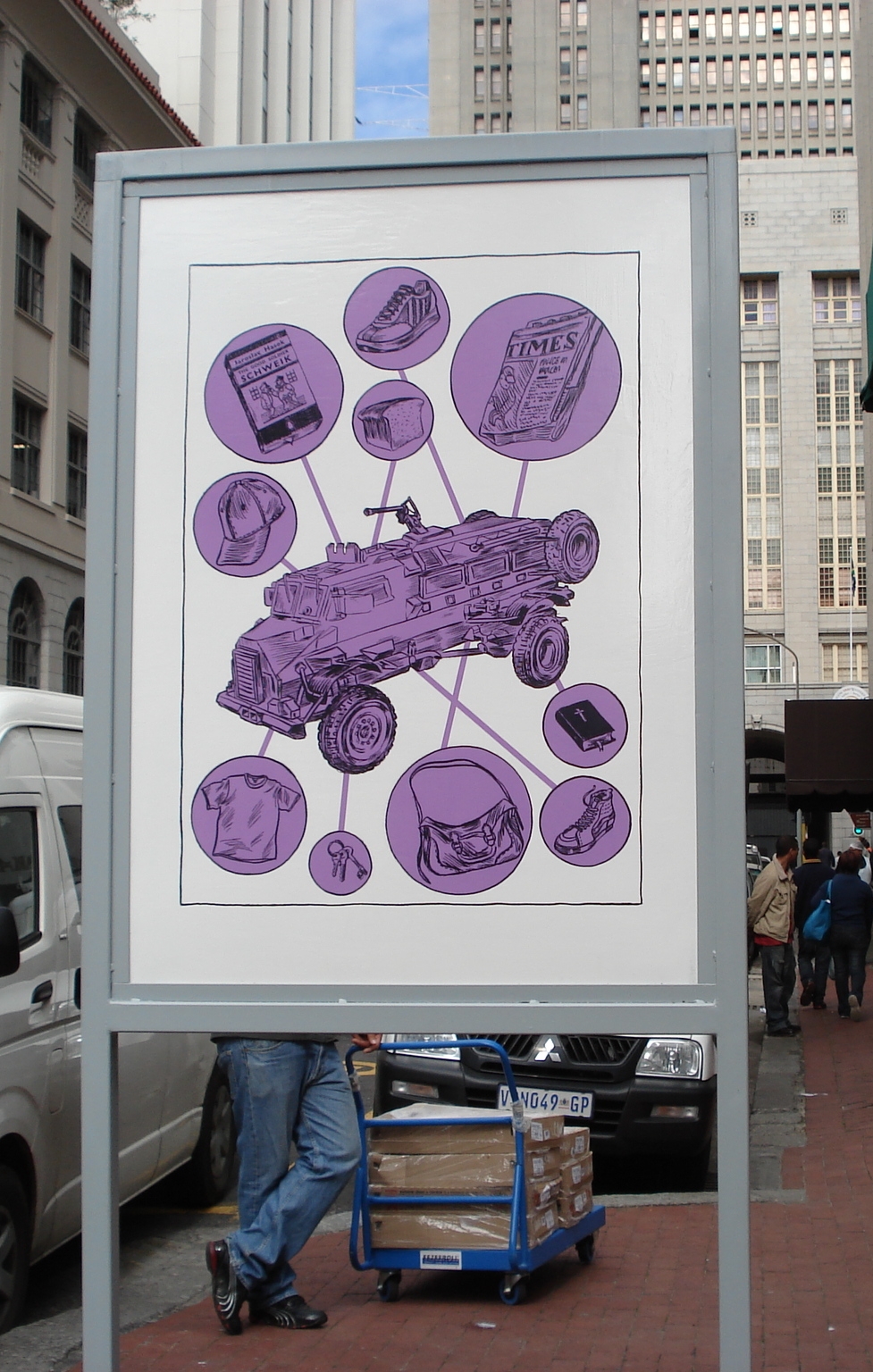

Subsequent to the building of these three monuments, a newspaper, The Sunday Times celebrating its 100 year history, produced a series of memorials commissioned from famous artists dealing with significant moments and individuals throughout the country, nine of which are in Cape Town. These are interesting because their focus often goes beyond pain and looks to celebrate moments of achievement - such as the memorial to a famous Jazz tune, Mannenberg, by the legendary Abdullah Ibrahim (by Mark O Donovan and Francois Verster), a commemoration of the first woman councillor of colour who came from District Six - Cissie Gool (by Ruth Sacks) a memorial to a significant cricketer of color, Basil D'Oliviera (Donovan Ward). They include two pieces that are often visited by tour groups because they are in easily accessed parts of the city centre - the monuments representing the race classification board (Rodrick Sauls) and the other commemorating the Purple shall Govern/Purple Rain Incident (Conrad Botes) an important moment of resistance. The City had little to do with the development of the pieces, but have now taken on maintenance of them. They are well documented with a special web presence including links to other content, very unlike the City built memorials.

A section of the slavery monument on Church Square.

Memorials to a Slave Past

The commemoration of slaves has taken much longer. A plaque has existed for some time close to the site where the Slave Tree once was, placed by a civic groups concerned with slave history, the December 1st Movement. In 2008, Church Square, close to the plaque, was redesigned from a parking lot into a square for the public and a memorial was commissioned by the City to slaves as part of the urban design. The winning piece was by two well known and experienced artists who have done numerous public art commissions - Gavin Younge and Wilma Cruise. The memorial has many positive elements, but was roundly criticized by stakeholder groups involved with slave history. However there was no attempt made to address concerns and the piece was constructed and installed as is. It stands alone as a piece in terms of interpretation, despite the Slave Lodge Museum and plaque being alongside it. Considering its major impact on the city, few people, tourists or locals are aware of the significance of slavery, and many outside of the Cape are unaware of regions slave history and how it shaped the city's large "coloured" population. Other cities with connections to slavery, for example in Liverpool, Nantes, Dakar, Accra, all speak to their slave past in museums and memorials that are strongly promoted as sites of commemoration and pilgrimage.

A priest blesses the ossuary of the Prestwich Memorial before the bones are brought in. Photo by Bruce Sutherland.

But the callousness related to the treatment to the history of slaves is evident in city's handling of the Prestwich Memorial. This is a space where he bones of former slaves found during the building of luxury apartments in Prestwich Place have been placed. Following a difficult protest by a group emerging from the December 1st Movement for dignified treatment of the human remains, an ossuary/memorial was finally built. However the memorial was later leased out to a coffee shop who have branded the venue extensively, and few now understand what the site's actual purpose is. The Prestwich Place Committee has continued to advocate, unsuccessfully, for changes, but does hold an annual commemorative night walk to celebrate the abolishment of slavery, which passes both Church Square and other Slavery relevant sites, ending up at the Prestwich Memorial. The fact that this walk is held at midnight does not help to expand the reach of the initiative to recognize slave histories, but it is held consistently and with greater reverence and is thus one important way civil society is keeping the memory alive. The city to its credit has done research and produced brochures on Cape slavery, but this has not moved into a more significant project to promote the story either to heal past wounds, to further understanding and thus foster social cohesion or to enhance visitors knowledge of the city.

Where to with Memorialisation?

The City has been planning a monument to Mandela, an icon who has relevance to all political parties and citizens for some time. It has led the renaming of many contentious streets, and has implemented various smaller projects to remember the past (more especially in Langa), some in partnership with affected stakeholder. But on the whole a project to remember and to work with the memory of difficult pasts - as a source of dialogue and healing, or even as a marker of history - has not advanced. The story of indigenous people for one has received only token attention during name changes and one contentious project - a bench dedicated to Krotoa an indigenous woman - was subsequently destroyed by Khoi activists as disrespectfull.

The Khoi Konnektion perform at the opening of the Prestwich Place Memorial. Photo by Bruce Sutherland

The issue is not helped by the fact that the previous Mayor and current Premier of the province, (also the previous leader of the Democratic Alliance) is controversially an apologist to colonialism. Moreover the DA is an uneasy party made up of many powerful conservatives, who were leaders in the old apartheid Nationalist Party, but it also has centrists and younger reformers, a number of whom are of color. It receives its strongest support and financial contributions from major companies and individuals, who have in the past supported and benefitted from Apartheid. It has been in power in the region for some time and to a large extent has shied away from responding to the past. While it could be argued that none of the other cities have addressed their context through memorials either, few are burdened with the long and very harsh history Cape Town has. Being the first and most powerful outpost of colonialism and as a key regional center for the development and implementation of Apartheid, it is both statistically, and by reputation, one of the most unequal cities in the country, it would do the DA well to show it is concerned with reconciliation, not just for itself, or the city, but especially for the broader country where racialised tensions have never been as high, or relations as acrimonious.

Mosaic memoria to student uprisings in Langa as part of a project to remember the neighbourhoods history

Conclusion

Memorialization can be a powerful cultural policy tool - an aid to story telling, healing, social cohesion and even, as a result of its link to tourism, economic growth. However it needs to be done well and have a consistent programme. Stakeholder engagement is critical throughout the process, not just at the end, since it needs to speak to core constituencies and be owned by them. The commissioning process thus needs to carefully planned. Its important in this, for pieces to be appropriately located and where they can be seen regularly by passerby. Budgets need to be set aside for interpretation (both on site and online), for activation (regular performative rituals), for education of communities around it and for maintenance. Ideally series of pieces should be curated to tell the broader stories of the city. The Memory Project shows that mayors can find ways to enable citizen participation, through broader campaigns aimed at social cohesion. However consistency is needed and budgets need to be attached to enable communities to be involved. In this way memorialisation projects, as vital pieces of ongoing dialogue between all citizens in the city, including a range of institutions in the city, academic, cultural, media, non-profit and business, can play an important role further reconciliation.