The Memorial as a Tool for Dialogue

Over the next few articles we will be discussing matters related to public art in cities, cultural justice and how people draw on their heritage to make meaning in their lives. There is initially a focus on some Cape Town cases studies, thereafter other cities. first we examine a common form of public art, its use in the memorialization of histories.

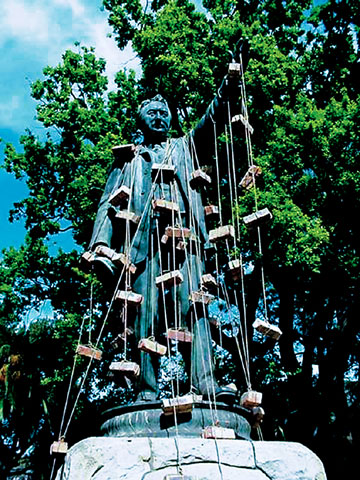

The Statue of Peace also called Sonyeosang. Photo from the internet

Memorials and monuments, usually sculptures, statues, plaques, street names, sometimes fountains, buildings or parks are some of the ways to mark moments of history in place. We walk past them daily and they often become part of the furniture of a space, with only some aware of their meanings. But even where we do not understand why and how they got there, or what or who its all about, they exert some sort of power over us, recognising that someone or something was so noteworthy it made people before exert energy and time to mark that person or moment. In some cases a piece will be activated over time through rituals, as is the case with the Comfort Woman pieces in South Korea, giving it meaning at special occasions, a tool of healing for South Koreans, and for advocacy (a way to confront the Japanese government to apologize). Sometimes the representation in a memorial may be negative to a section of the population. In such cases collective pain may build up over time about the piece's meaning until there is a public response. This counter response, to the memorials official meaning may result in an urge to damage it or to remove the item from the public gaze.

A toppled confederate general - photo from the internet

By now we are all used to seeing countries deposed of oppressive rulers, whose people tear down statutes that glorify these (or other related) individual/s. This happened spectacularly with the fall of the Soviet Union and in many countries who experienced the Arab Spring amongst others, where sculptures of various communist leaders and dictators were taken down. More recently we saw a push to remove sculptures memorializing confederate generals in the USA - this comes amidst growing violent racism against people of color in that country, oftentimes perpetrated by its own police. The case is instructive because it exposes the key rationale for the erection of these pieces in the first instance. These were not pieces that were built simply to remember past heroes and moments, They were mainly built during the time of the Jim Crow Laws (1877–1954) and the Civil Rights Movement (1954 - 68), as a calculated revisionist history writing exercise, done by the United Daughter of the Confederacy, the main entity putting up these pieces. They were done with a clear agenda to intimidate black people using public space, by glorifying and perpetuating an idea of white supremacy. Thus memorials here were used as a force of oppression. Although a number of these memorials have been removed, many still remain, with a, sometimes violent, insistence by right wing groups that these represent their cultural history. Those who have been involved in advocating the removal of the works have made it clear that they will not accept the rising fascism in the country and come from a wide range of interest and ethnic groups, not just black. Thus the case shows that acting to remove memorials, while it may set up difficult contestations, can have potentially positive responses, bringing people into dialogue and fostering acts of solidarity.

Maxwele's ritualised protest which started a movement. Photo from the internet

Rhodes Must Fall

A few months before this moment in American History, and seemingly an influence to it, South Africa came head to head with memorials as representations of oppression. It started at the University of Cape Town (UCT) and would impact on a number of tertiary institutions around the country as well as some prominent ones internationally, including Harvard and Oxford. The Rhodes Must Fall movement started on 9 March 2015 after a student, Chumani Maxwele , threw a bucket of faeces in a ritualised performative act onto the statue of Cecil John Rhodes. Rhodes was an arch colonialist, capitalist, a prime minister of the region, racist and one of the richest men in the world at the time of his death. He had bequeathed the ample land for the building of the University as well as money. His statue took a prominent position at the center of the university, next to the student union and was one most students had to pass daily. Within a short time, Maxwele's act against the pieces led to a mass movement for the removal of the statue, together with a call to decolonise the curriculum at UCT and at universities in most other major cities. The statue was removed a month later, but the fire had been lit for the broader campaign and protests, which morphed the following year into Fees Must Fall, again a national movement. This broader campaign extended beyond curriculum and the hiring of more black lecturers, to include protests against the high costs of education and of residence fees and against the privatization of certain services at universities. The latter had created job insecurities for cleaners and security guards, amongst others. What started as a response to a statue of an individual who represented all that was oppressive and malignant from colonial South Africa, became a movement to change not just the universities, but was a response to the deep challenges in broader South African society.

But the movement was not without its challenges. For one, there were various acts of violence and vandalism at a number of universities. Many outside the academy found it difficult to see beyond these, to the core issues student leaders were actively calling for action on. Yet despite these difficulties the Fallist movement has been important both inside and outside the tertiary institutions. it has conscientised younger people about a range of key societal issues and helped build organizational and advocacy skills in the process. Within the universities it created a space to deal with simmering concerns by younger and black academics about the curriculum. Its forced older academics to think more carefully about what they have been teaching and how they have been teaching The kinds of debates it has fostered between academics and students, has led to important fruitful shifts in the academic body and student body. The public has shifted negative attitudes about young people being apathetic and some have been forced to think about the kind of country that the young will inherit. As a country wide protest, it has forced government to consider its failures not just in terms of tertiary education, but also in respect to broader issues. It came at a particularly difficult political moment in the country, where the president at the time, Zuma, and a cohort of his supporters had been openly abusing the country's coffers. Thus it was, in many ways, another pertinent response to a ruling party which had become complacent about an uncritical support from the population. All this out of a response to one statue.

The Rhodes Statue during protests - photo from the internet

Memorials - Beyond the University

The protest against the Rhodes statue did go beyond this particular memorial to a limited extent. There were defacements of a number of colonial statues, and some calls for removals. However little of significance came of it. South African cities are filled with colonial memorials, as well as many that were put in place just before and during apartheid, though a number of the more hated apartheid statues were removed post change in the early 90s. New heritage laws protect the remaining pieces and there are strict processes when it comes to removing them. The Rhodes statue was an anomaly since it belonged to the university and not the state. As part of the negotiated settlement for change, it was agreed in principle to find some kind balance in society - to keep the old pieces as an act of reconciliation and to build new memorials that spoke to previously unrepresented histories as acts of symbolic reparations. The results have been patchy. It is a difficult thing still for people of colour to confront memorials of various mythologized colonial heroes on a day to day basis, while at the same time having few of their own heroes recognized in similar ways. Even if there is no backlash against them, its presence is still felt and what it signifies resonates. In the next article we will look at some of the pieces that were erected in Cape Town that seek to add new narratives into public spaces.

There have been other attempts to confront memorials of the past, through activating them. In 1999, the public art collective Public Eye produced a city wide campaign to adjust many of the colonial memorials during the Cape Town One City Festival. This one off event called PTO (Please Turn Over), was done in a simple, non destructive manner (pictured below). Each piece was restored to its former state within a few days as required by law. It was an interesting ephemeral act, and while some pieces were powerful, many of the pieces had relatively innocuous commentary attached to them. Its hard however to understand what the response was to the project since few interviews were done at the time, nor was there a concerted follow up to the project. Thus the project shows a potentially interesting way to foster greater dialogue between the public and the pieces, displaying again that creative campaigns can elicit responses and spark dialogue. The question though is what appetite (or ability) do authorities have in opening dialogue about such issues, even in a relatively controlled manner? Once the pandoras box is opened, as we saw with Rhodes Must Fall, the impacts can be significant.

Next Week

In the next piece, I will be looking at some of the monuments built post-apartheid in Cape Town, exploring how they came to be and what the commissioning and development processes suggest could be ways to approach future memorialisation.